Storytellers: Marv Wolfman and George Perez

Publisher: DC Comics

Year of Publication: 1982-1983

Page Count: New Teen Titans 26, 28-34, New Teen Titans Annual 2 (222 pages)

What I learned about Writing/Storytelling:

1. There’s an old Japanese movie Rashoman, where everyone is interviewed about an event and recounts a different version of what happened. A million different stories have been written riffing on it, and Marv Wolfman comes up with a clever twist on the formula in in Teen Titans 33. A super-villain named “Trident” is found murdered, and the Teen Titans sit around discussing the mystery. It turns out many of them have fought Trident on separate occasions, but, they realize, none of their stories add up, Trident appears to have had different powers on different occasions. The Titans come to realize there must be more than one “Trident”, and they eventually track down the second criminal. The demonstrates a method of playing around with an old formula.

What I learned about art/storytelling:

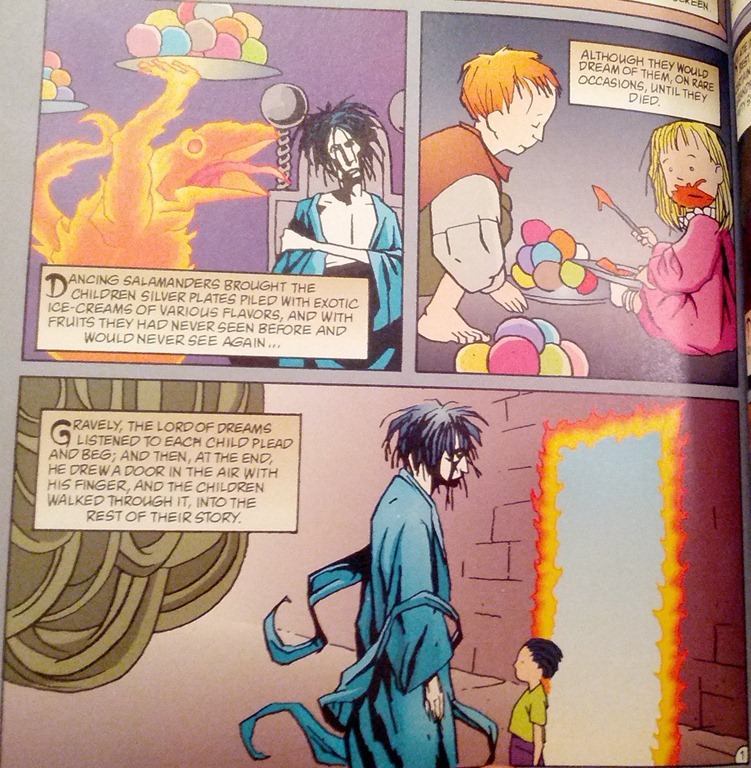

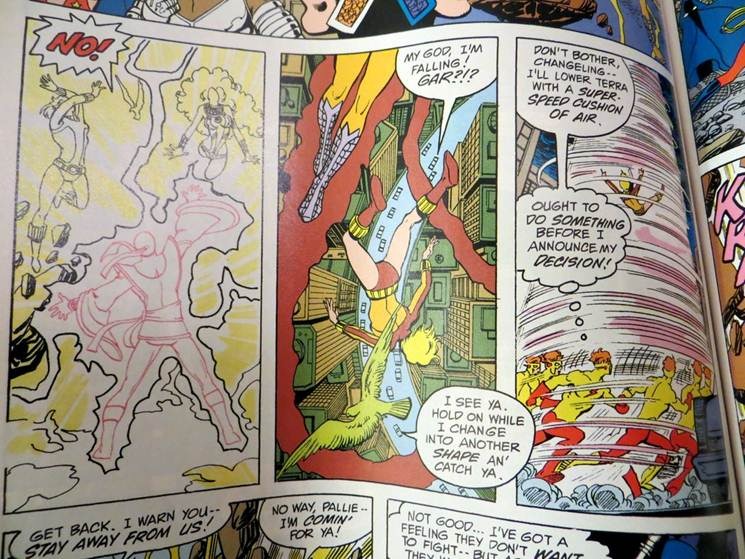

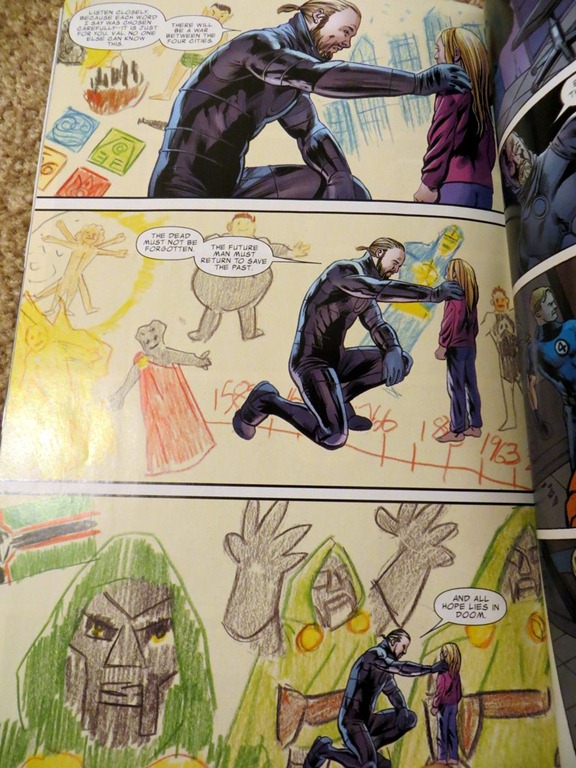

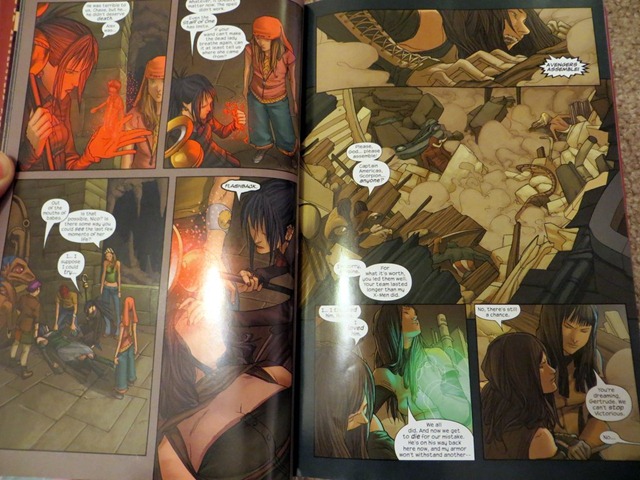

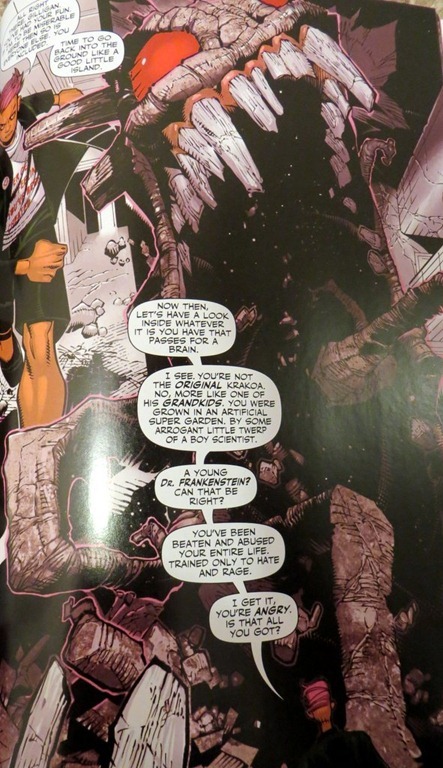

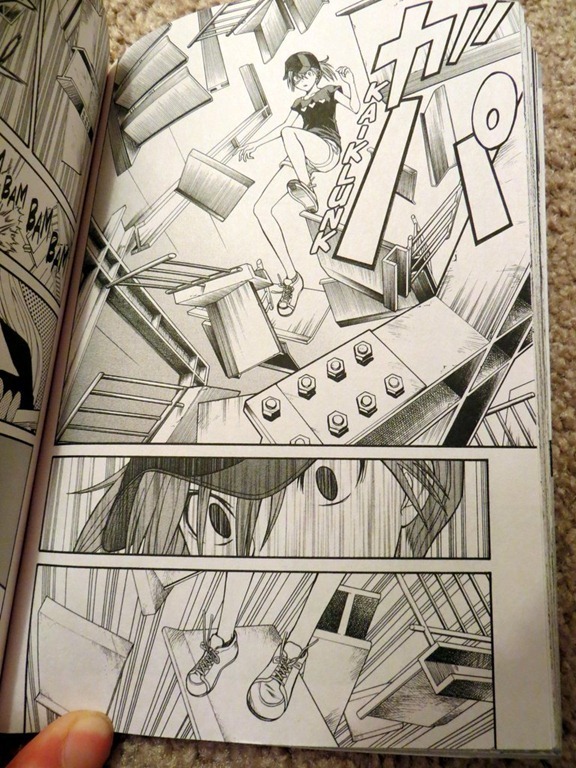

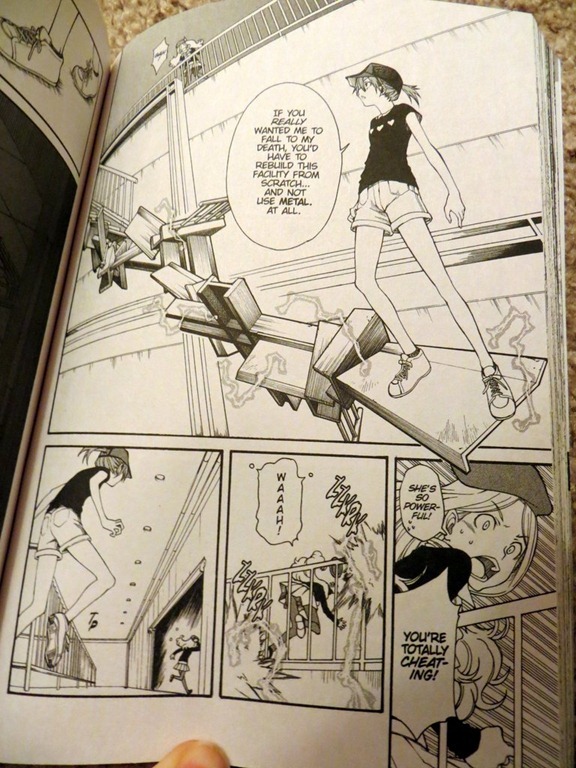

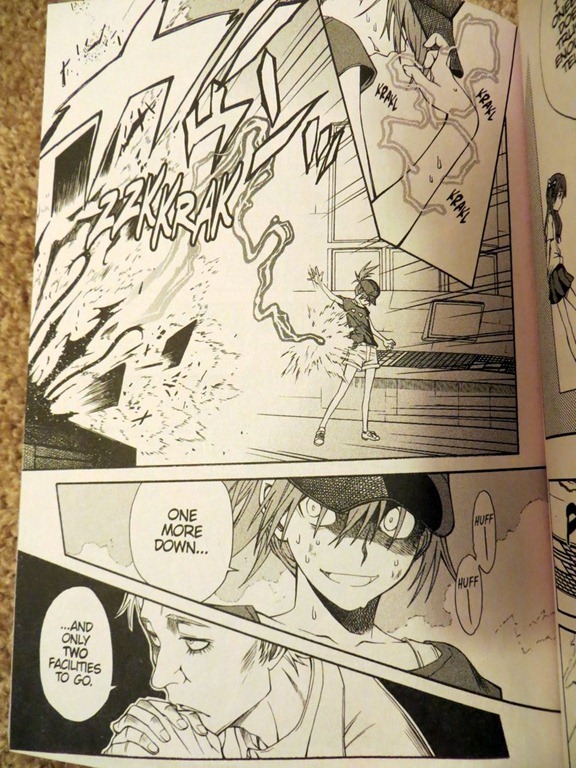

Perez is definitely a pro, and the camera angles have a lot of diversity and are a lot more interesting than in the JLI art I discussed earlier. For example, in the image below, due to a savvy choice of camera angle, we get a powerful image and a true sense that Terra is falling to her death:

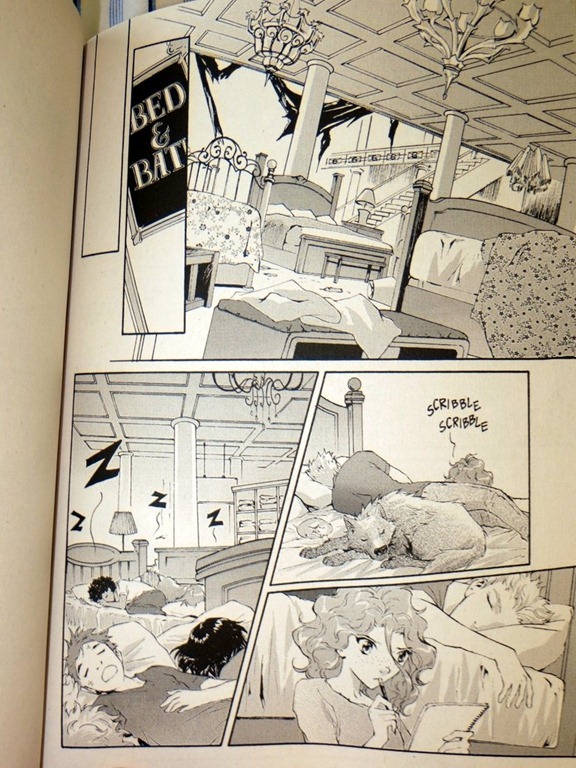

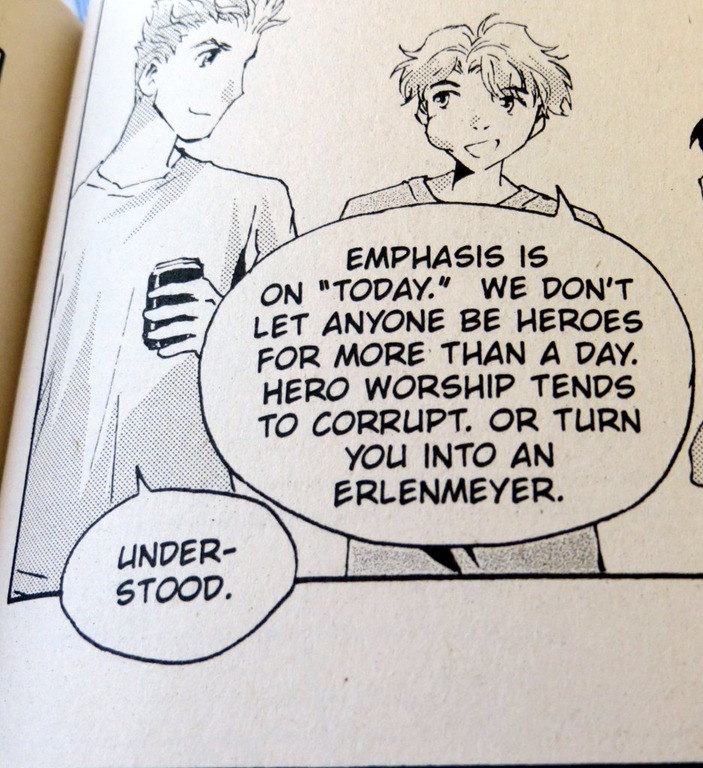

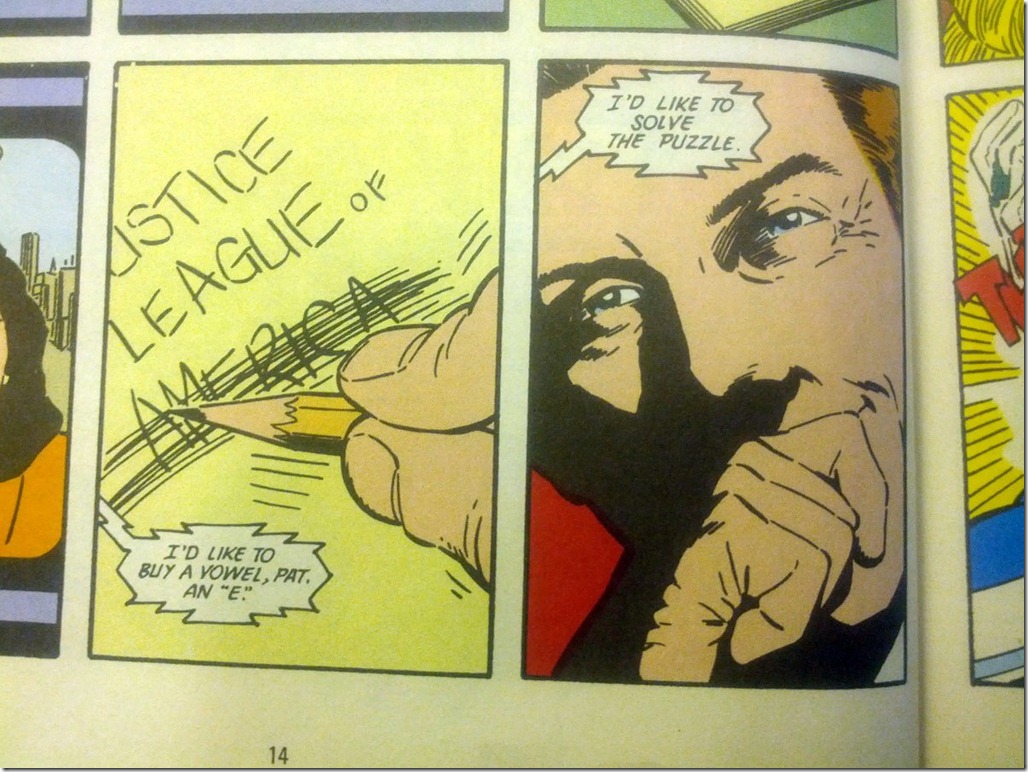

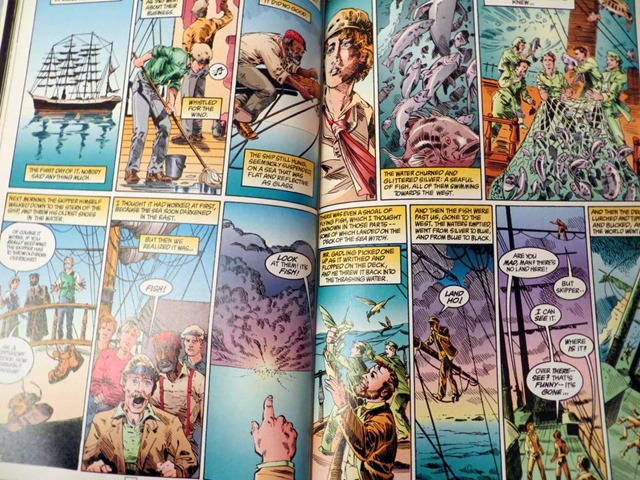

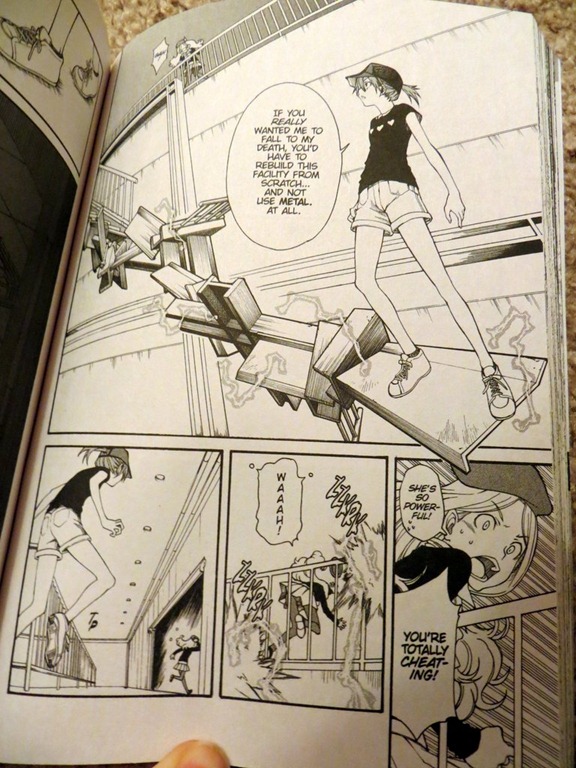

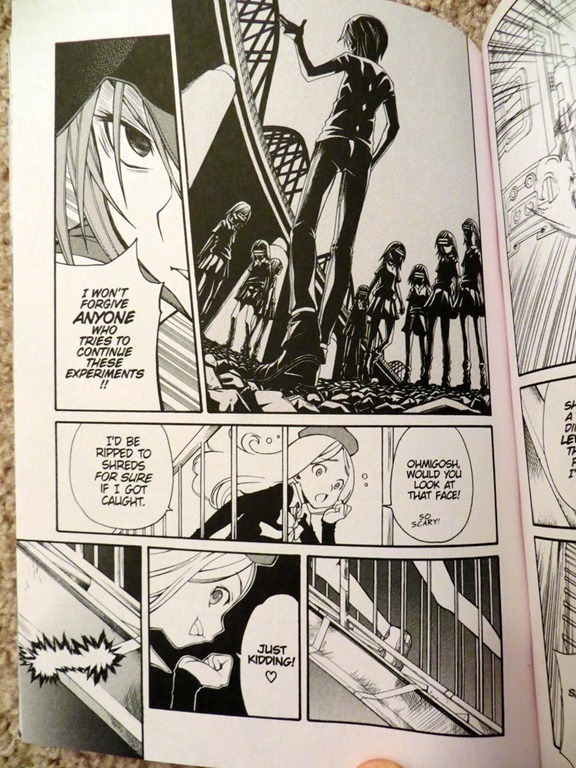

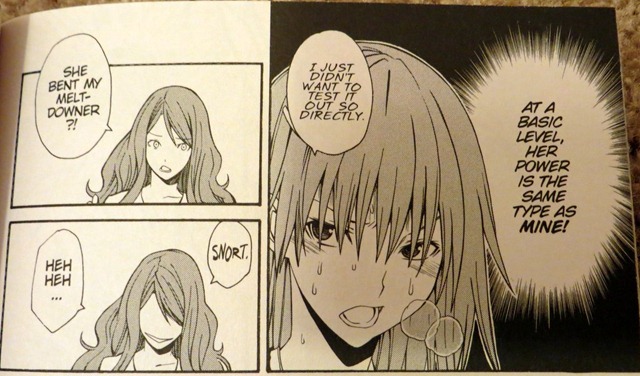

Here’s a fun little sequence:

I would never have consciously noticed this if I wasn’t looking at it closely for purposes of this review, but the panel with the white background runs behind the other panels, given a sense of open landscape. It works fine, while sticking to a fairly readable, traditional layout.

Recommendation: C+

Notes/Reviews/Synopsis:

Yeah, this isn’t a very good comic. I know this was DC’s most popular comic back in the day. That it’s historically important, and even one of the first superhero books with interesting female characters. That said… I didn’t find it fun to read at all.

Given a story that could be told in 20 panels, this team chooses 80.

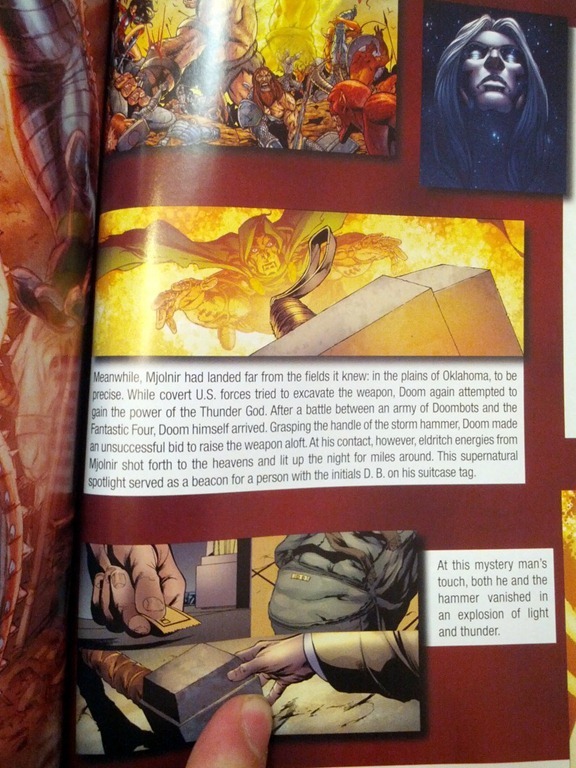

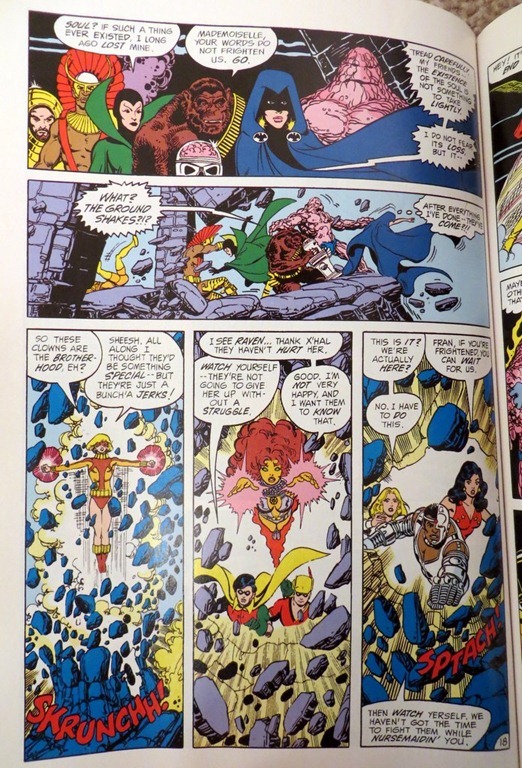

For example, the opening plot involves a group of villains planning to abduct Raven for a nefarious scheme. It’s a serviceable plot, but instead of getting to it, we have a scene of the villains fighting a different group of villains, a scene of the villains apparently getting killed, a scene showing the villains survived and are preparing to strike at Raven, a scene where they attack Raven at Titans headquarters and get their asses kicked, a scene where Raven runs away due to teen angst, a scene where the villains escape capture after the fight, a scene where the villains ambush Raven in the church where she’s meditating alone, a scene where Raven escapes, a scene where the bad guys track her down in the city, yet again a scene where the Titans come to Raven’s rescue but lose the fight. And finally, we get on with the plot: villains have kidnapped Raven and the Titans come rescue her:

That page was fun enough… but ooooh, the tediousness to get to it.

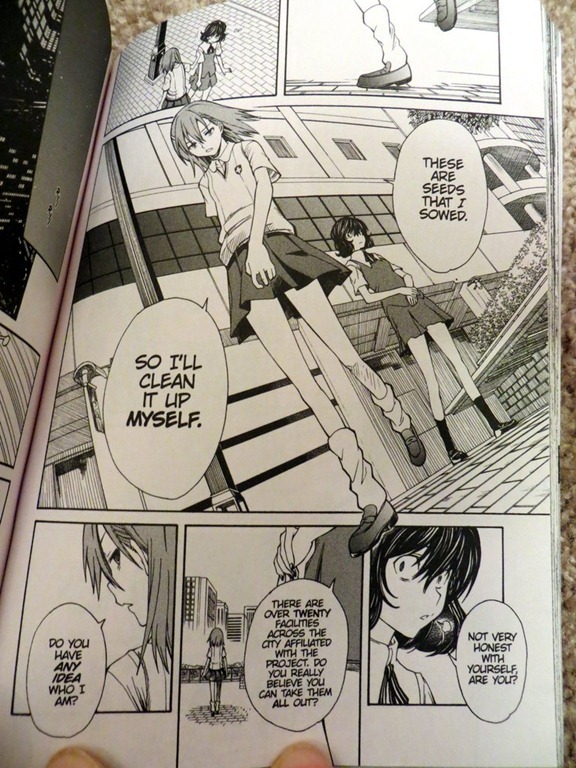

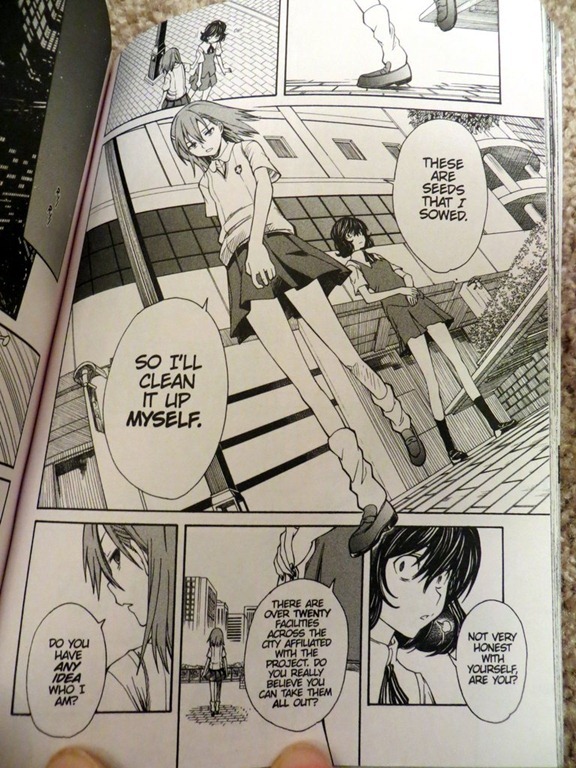

The character stuff with Terra was neat, but then it turns out, apparently, it was all a lie and she was a wolf in sheep’s clothing all along. I think it would have been better if they did some sort of Total Recall fake memory thing with Terra. What’s the point of all of these scenes, building character, if it’s all just an act?

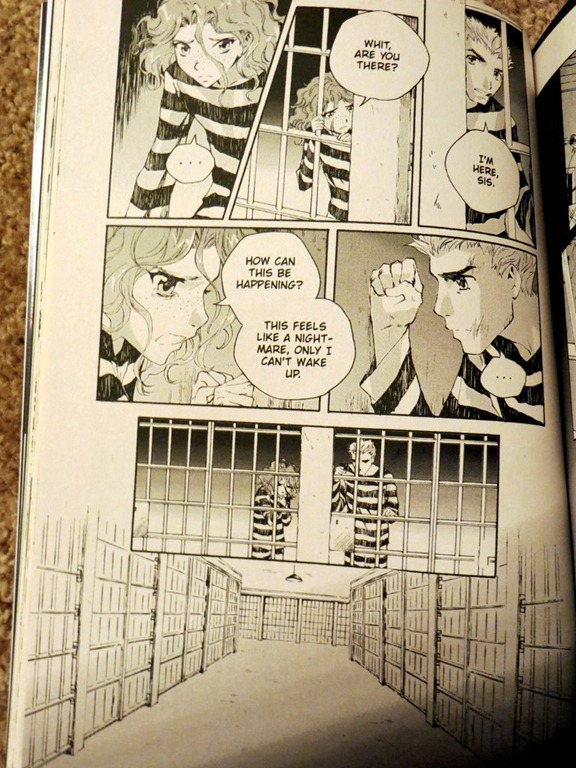

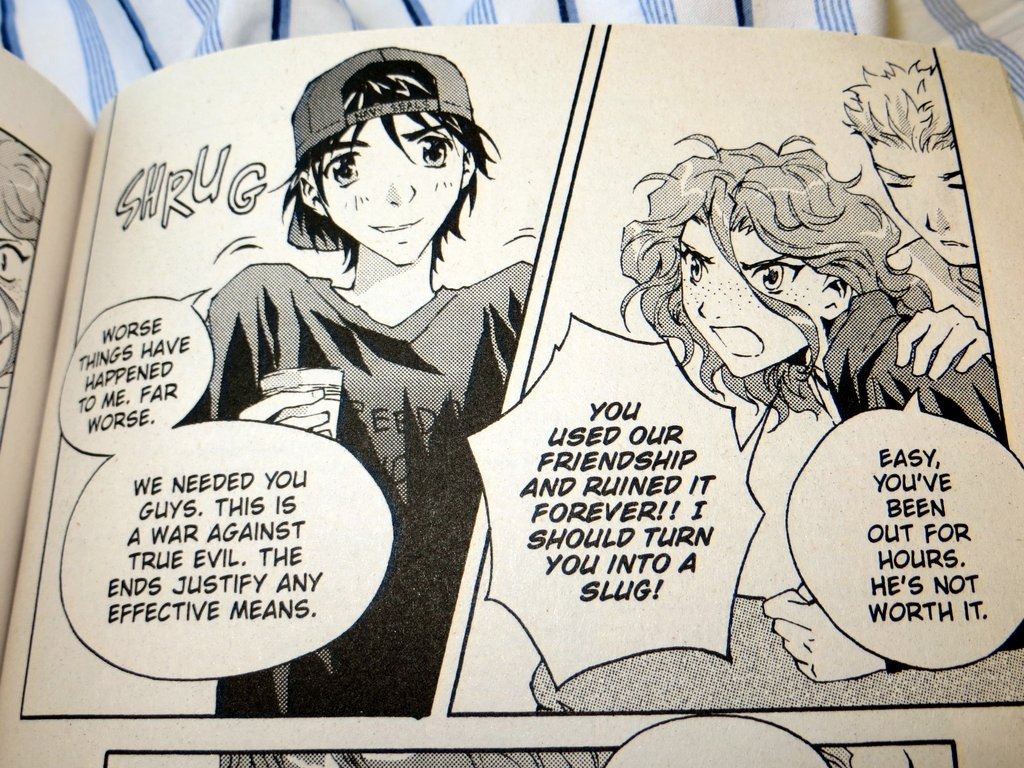

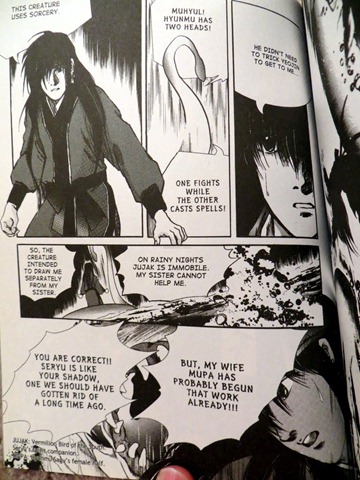

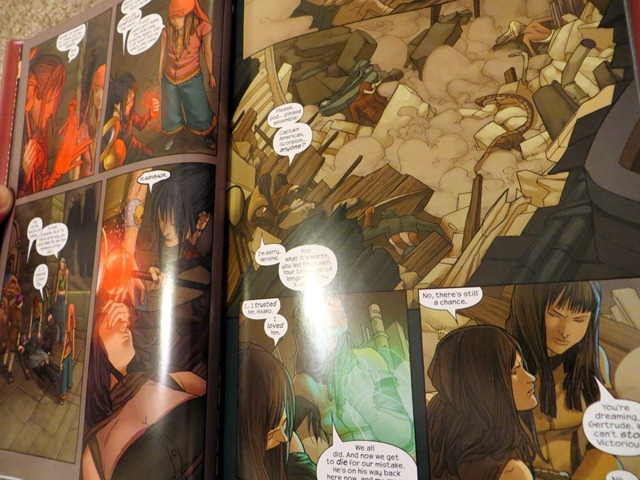

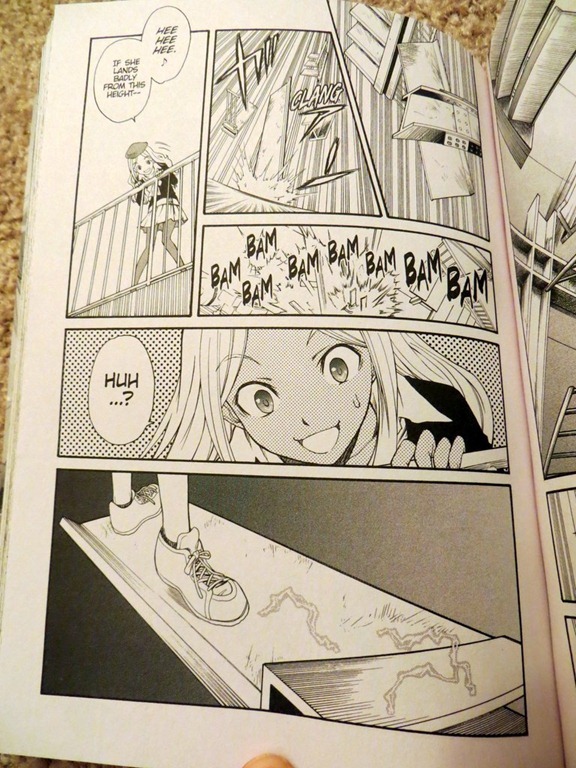

I guess it’s possible a villain could generate alligator tears at will, as Terra does here, apparently:

but.. it sort of ruins what little emotional resonance there is in the book upon rereading.

There are other issues, such as the need to wedge in soap opera melodrama as much as possible for it’s own sake.

When Raven complains every issue that that it’s hard to control her emotions, and Kid Flash complains every issue that he’s thinking of quitting the team to focus on college, it becomes wearisome and you want to shout “For God’s sake! Turn evil or don’t turn evil, leave for college or decide to stick around, make a decision,any decision, just stop your whining!” Reading an issue only once every 30 days back in the 80s, this might have worked better, you were following the characters on a journey, and it was less about the quality of the writing, per see, but more about how the characters were growing up with you.

![01923d936af86ae7c0e4b60f42e71b26[2] 01923d936af86ae7c0e4b60f42e71b26[2]](http://scottdubin.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/01923d936af86ae7c0e4b60f42e71b262_thumb.jpg)