Storytellers: Ed Brubaker with Brad Rader

Publisher: DC Comics

Year of Publication: 2003

Page Count: Collects Catwoman issues 5-9.

What I learned about writing/Storytelling:

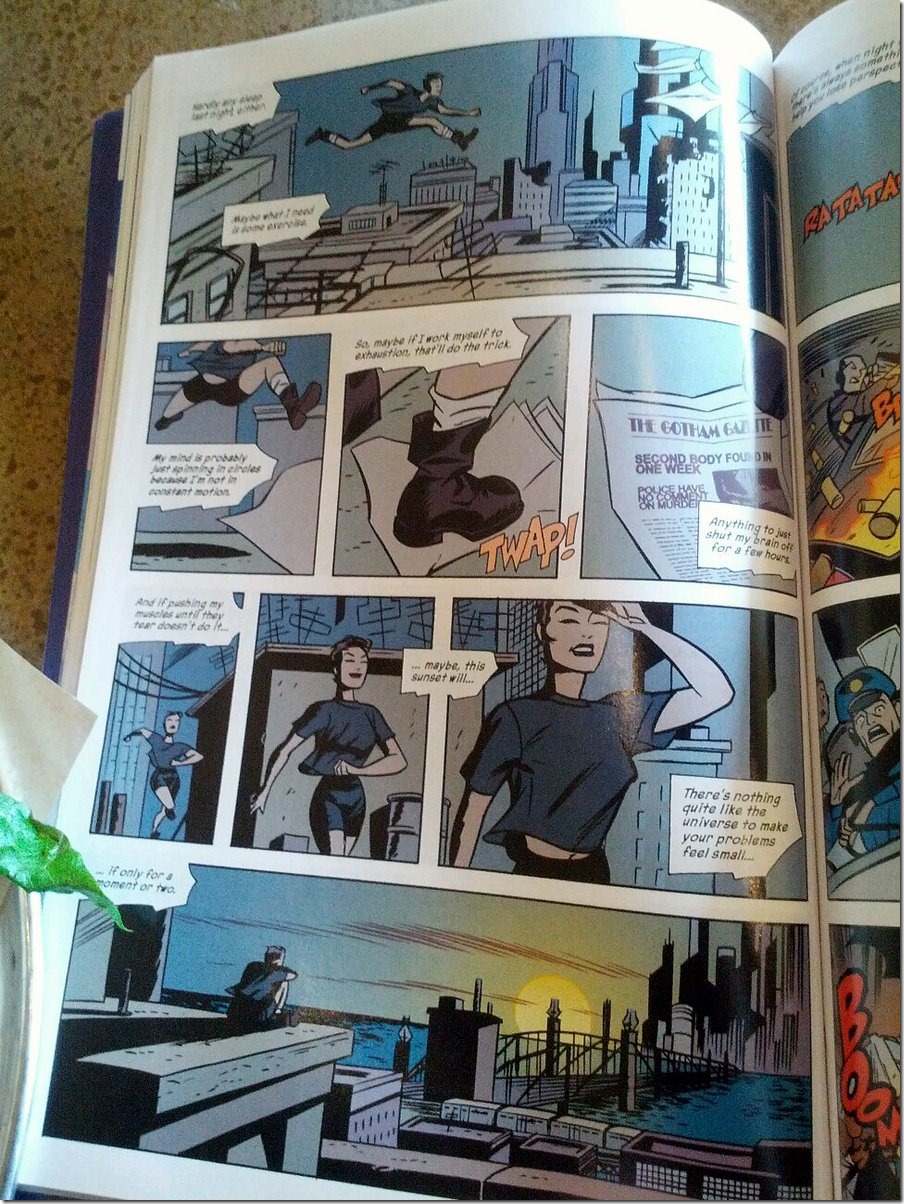

Darwyn Cooke is gone, but the motif of pages consisting of four rows remains, which suggests this might have been Ed Brubaker’s innovation, or maybe Cooke came up with it with it and Brubaker and the new team continued it.

In Catwoman #5, Brubaker does some tricky stuff with flashbacks and structure that seems worth looking at:

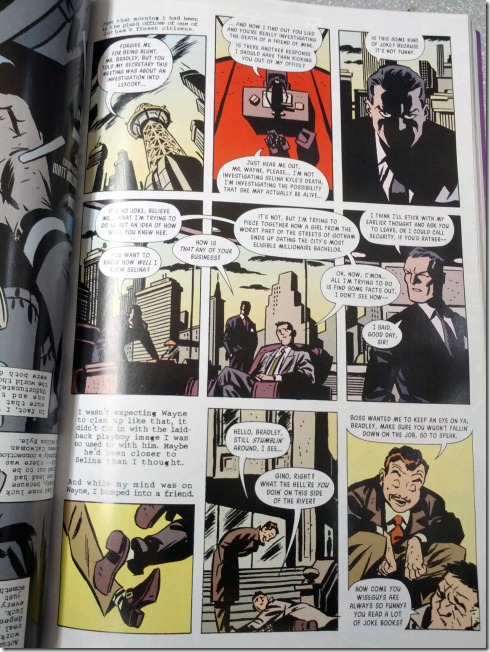

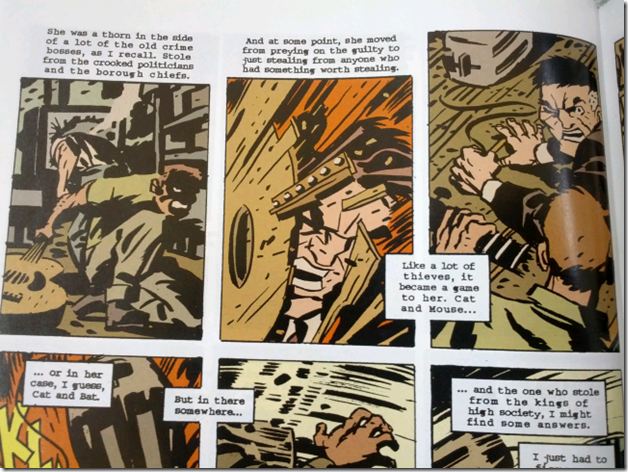

1. We start in the present, on page 1, as the cops interrogate a criminal named Dexter Garcia. He begins to tell the cops his story, saying “I ain’t even sure I know where the beginning’s at…” the reader turns the page and:

2. The text says “a week and a half ago”. We cut to Catwoman jumping on rooftops at night. She break into a hospital and visits an unconscious boy named Brendon. She says “Aw Brendon…You really went and did it this time, didn’t you?” This takes us to page 3. The reader turns the page and:

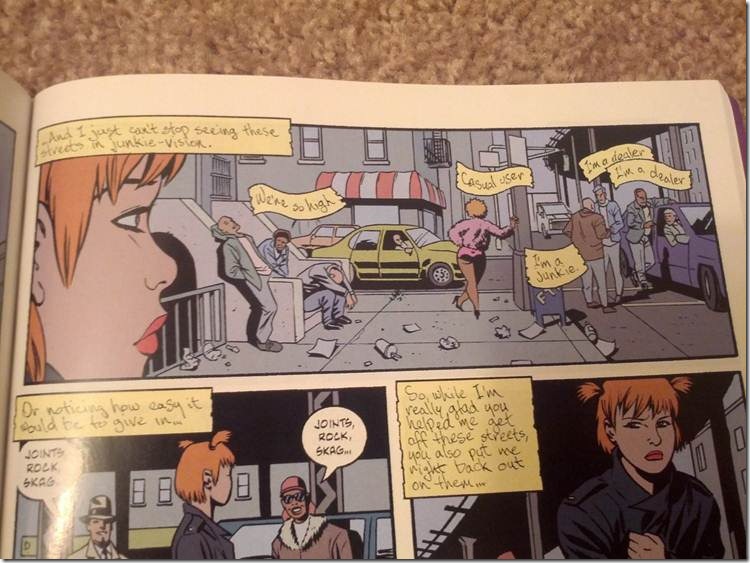

3. Catwoman begins to narrate, introducing an earlier scene with Brendon before he was in the hospital. She visits him as Selina Kyle, because she used to know his mom back in the day. Selina learns that Brendon is involved with drug runners, the whole backstory about how the drug runners operate is explained to her by her friend, Holly, after meeting Brendon. This runs on pages 4-7.

4. The very last panel on page 7 takes us back to the hospital scene. We learn the boy suffered injuries while running drugs. The next 8 pages (pages 8-15) take place after the hospital scene, with Selina staking out the drug organization responsible for Brendon’s injuries and trying to get Dexter Garcia to turn on his boss, Mr. Dylan. Selina confronts Garcia and says “It’s time you and I had a talk” to Garcia… then:

5. Time jump ahead, on (pages 16-18) Selina is pleased with how things turned out with Garcia, but the reader doesn’t yet know what happened. Selina is then approached by private eye Slam Bradley, who tells her Garcia did something bad. We have an interwoven flashback of Bradley telling Selina how Dexter Garcia tortured Mr. Dylan after killing Dylan’s body guards. Dexter was then taken in by the cops.

6. Then Selina starts explaining her conversation with Garcia to Slam Bradley (the one the reader didn’t see) and we flash back to Selina’s conversation with Dexter. Selina was just trying to get him to turn himself into the cops, not torture his boss. This flash back starts on page 19 and runs to page 20.

7. Page 21 and 22. Back to the opening scene with the interrogation. We find out the cops doing the interrogation are corrupt, and are going to kill Dexter on behalf of their boss, Mr. Dylan. Mr. Dylan vows to go after Catwoman if she causes more trouble. The final scene is Catwoman and Slam Bradley talking, with Catwoman mourning what happened to the boy, who is not expected to recover.

This is a really tricky structure with a lot of time jumps, but the story itself isn’t hard to follow. I wonder if the line “I ain’t even sure I know where the beginning’s at” is a sort of meta wink wink line as Brubaker was weaving the nonlinear story.

Presumably you can only write a story that jumps around like this if you plot it out in advance. I think Brubaker uses this structure to build drama. Why are cops interrogating this guy, we wonder, during the beginning scene, since we’ve been thrown in the middle of the story. When Selina breaks into hospital to visit the kid, we wonder what happened to the kid, then later find out. The structure allows the drama to be shown before the story’s quieter moments.

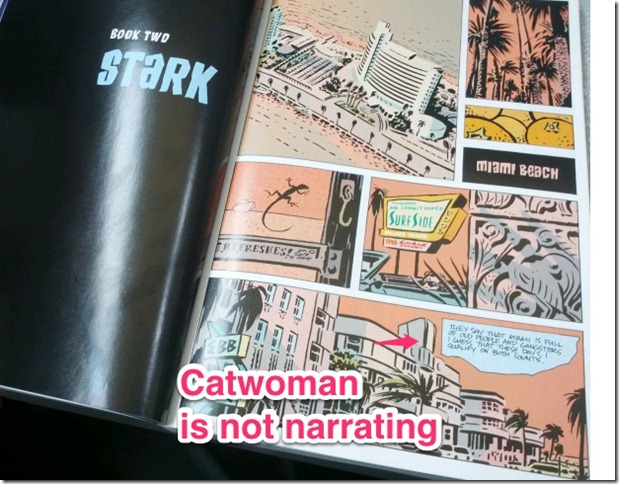

Other things learned (for the rest of the issues)

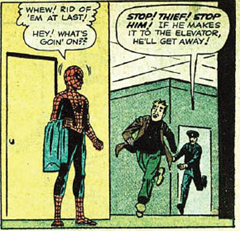

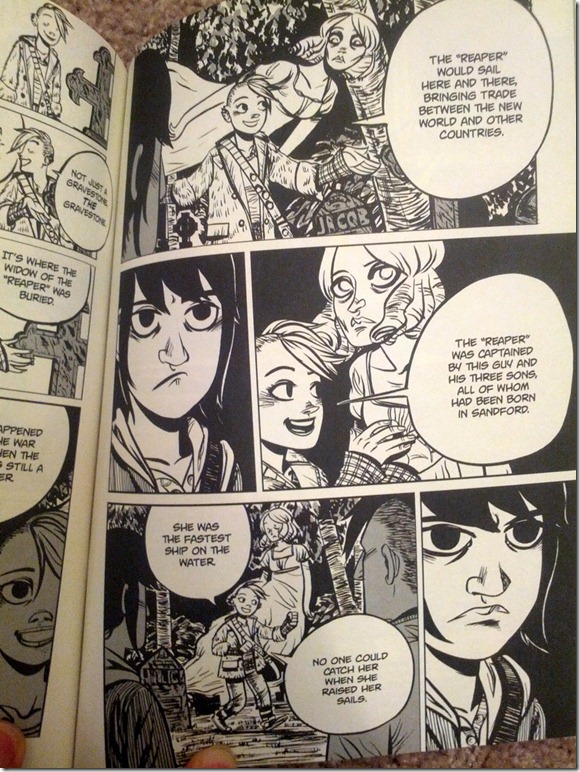

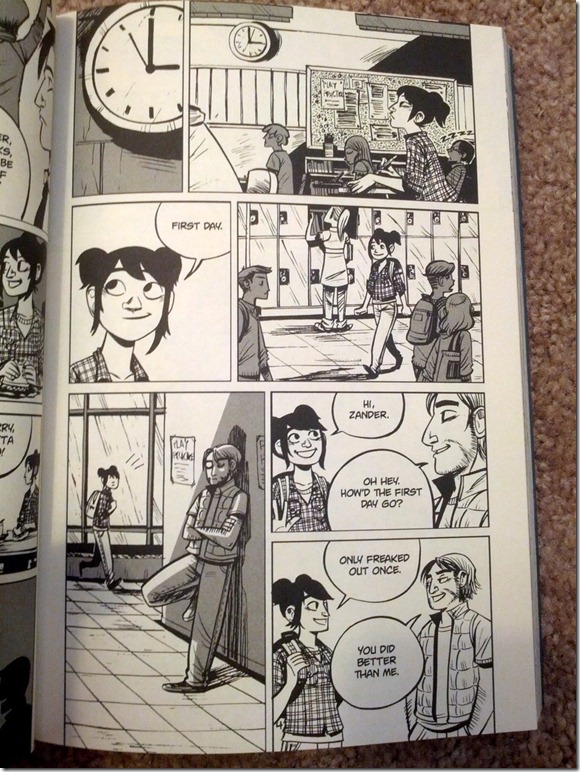

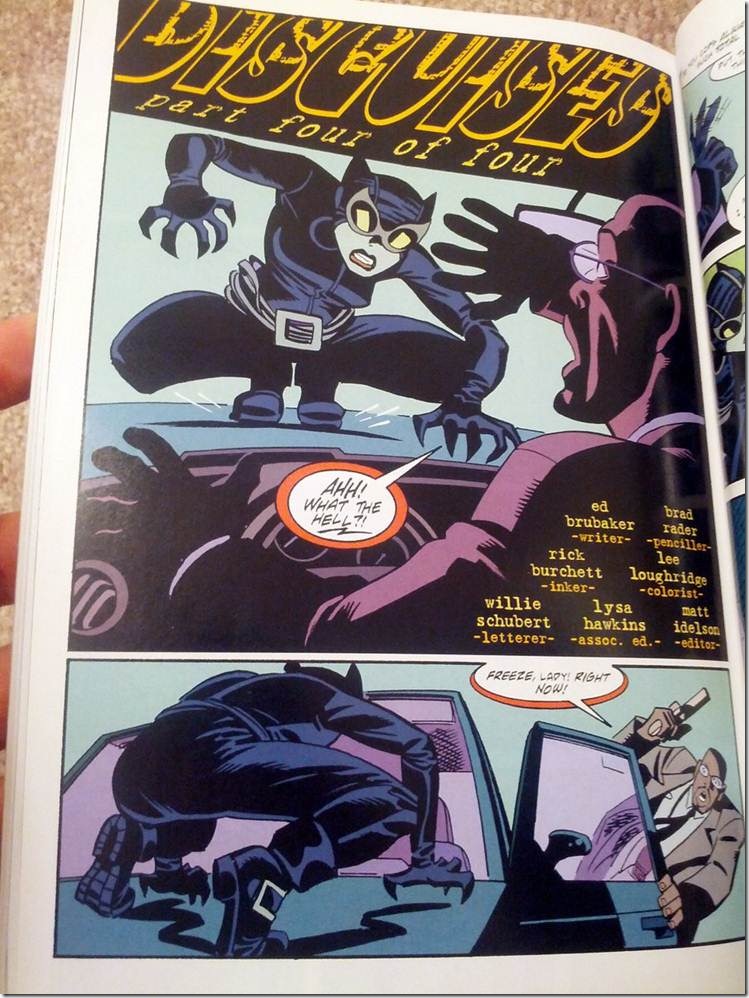

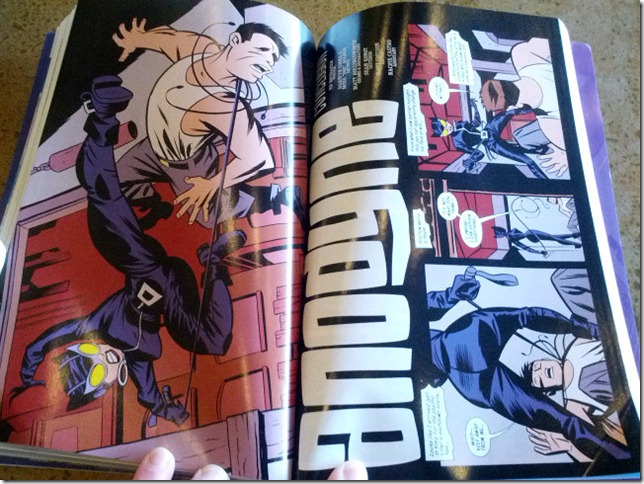

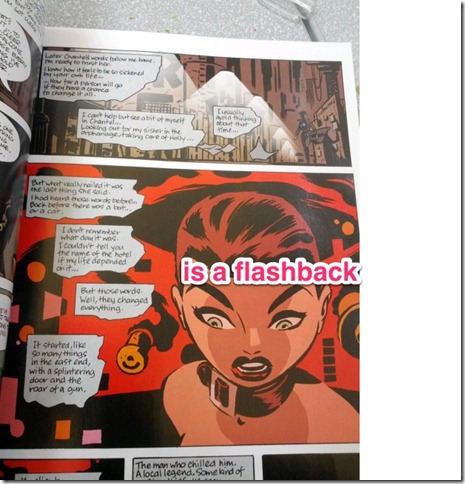

It’s the oldest trick in the book, of course, but Brubaker makes use of opening splashes (or big panels that are close to a splash), though in the following example he holds off until page 4. Here’s page 3:

Then you turn the page:

This is a cool effect, and its sensible to wait until page 4 so you can build up an opening scenario before Catwoman’s appearance.

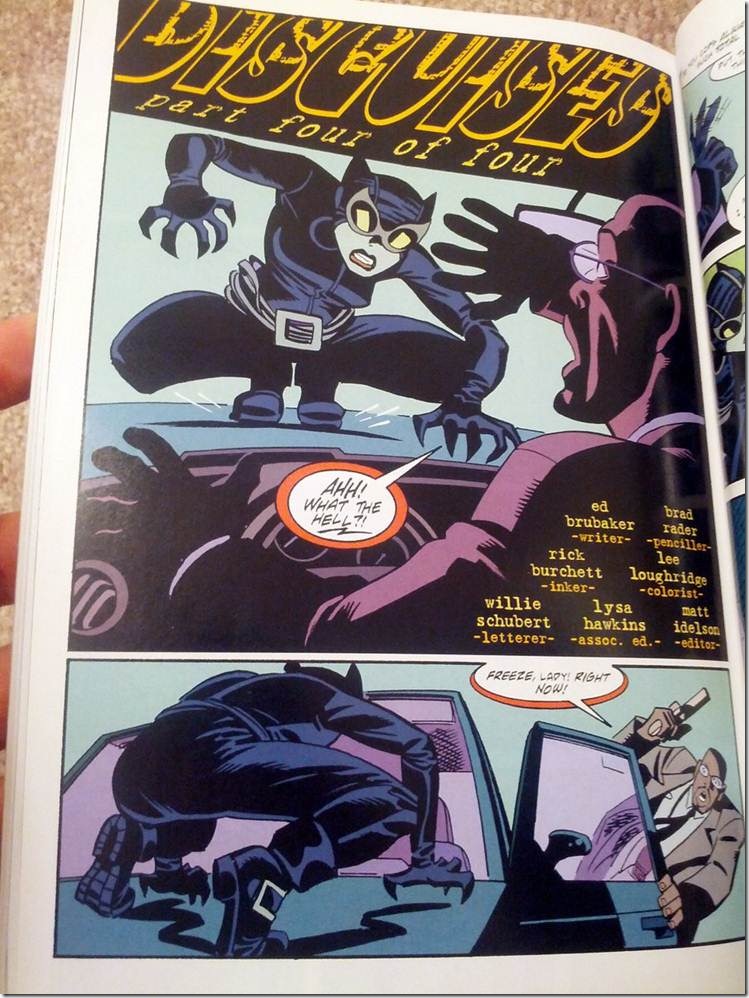

Other writing stuff: There’s a bit where Selina and Slam Bradley come up with a plan to take down some corrupt cops. The reader doesn’t know what the plan is, and we discover it as it unfolds. I think there’s basically two ways to do that sort of “plan” based story: You either have the audience know what the plan will be, then the plan goes wrong, or you hide the plan from the audience. In this instance, Brubaker hides it, and the reader is pleasantly surprised to see just how Selina kicks ass.

I enjoyed, in particular, that the plan revolved around Selina stealing something in a very tricky way, because it’s cool to see her villainous “gimmick” used against the bad guys. It’s good to see her do something specific to her character, rather than just punching people.

What I learned about art/storytelling:

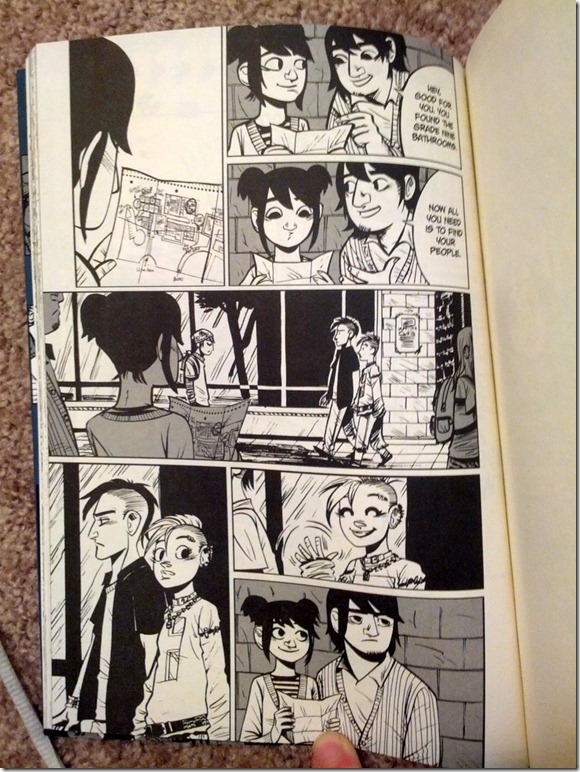

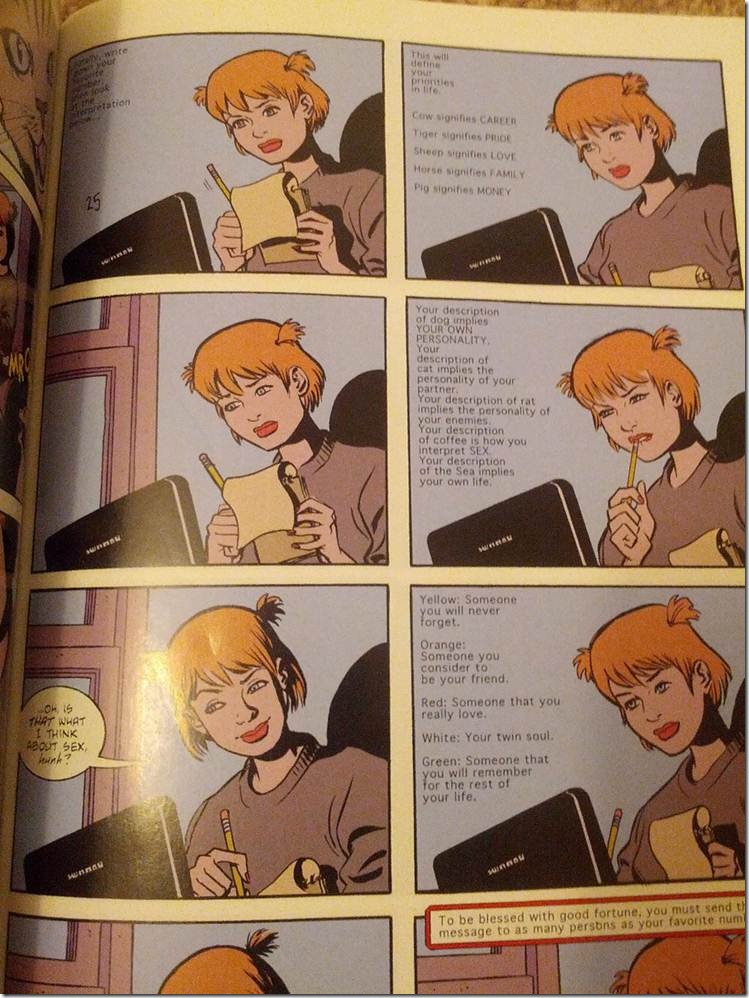

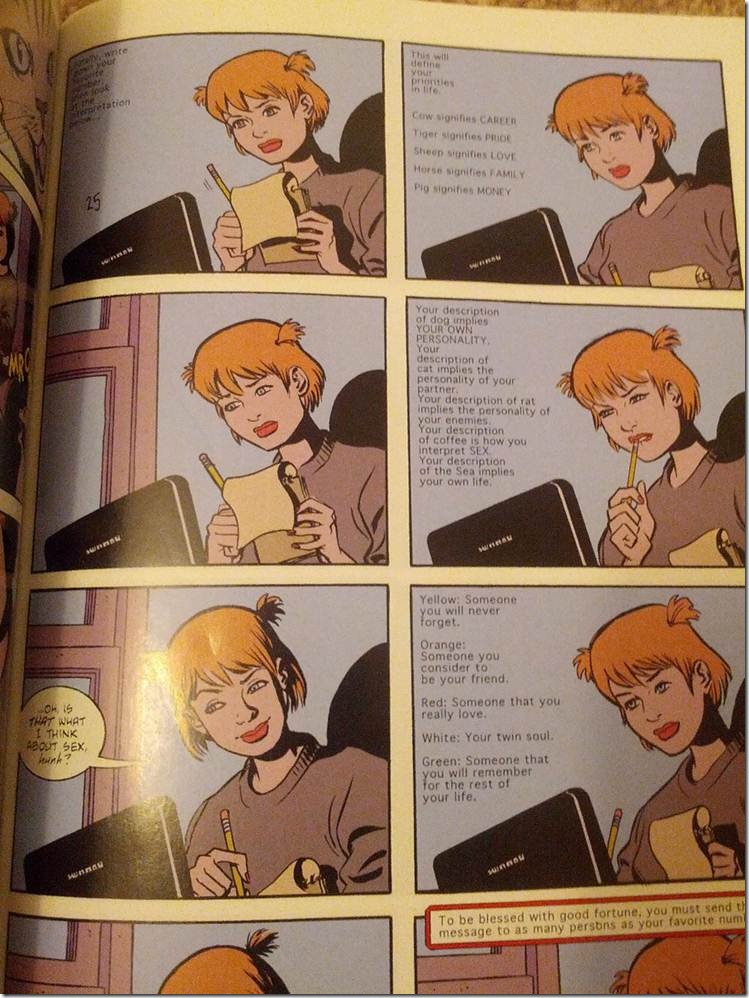

You get the sense the creative team is testing the boundaries of the medium. There’s a neat sequence with Selina’s friend Holly taking an email survey, and text appears in the background, showing the email:

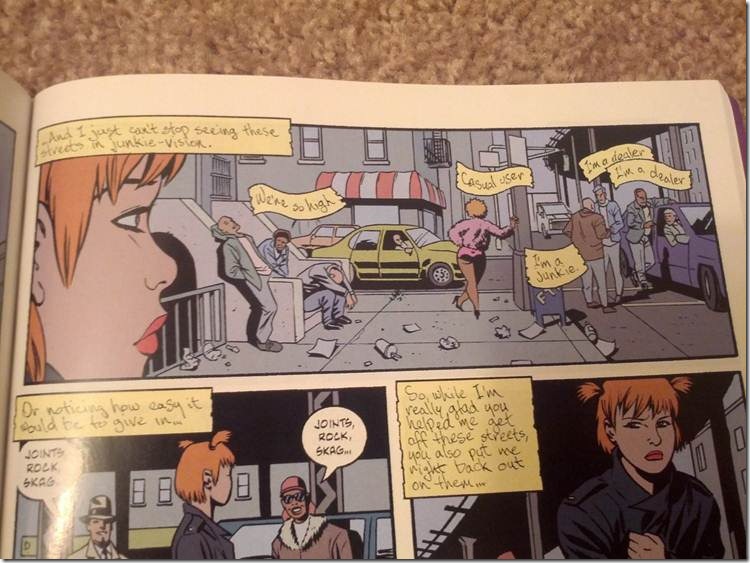

This is from a sort of “day in the life” issue starring her friend. They do a montage sequence of Holly’s observations about various people. They use cursive for her narration and spread it around, which is an interesting technique:

Recommendation: B+

Notes/Reviews/Synopsis:

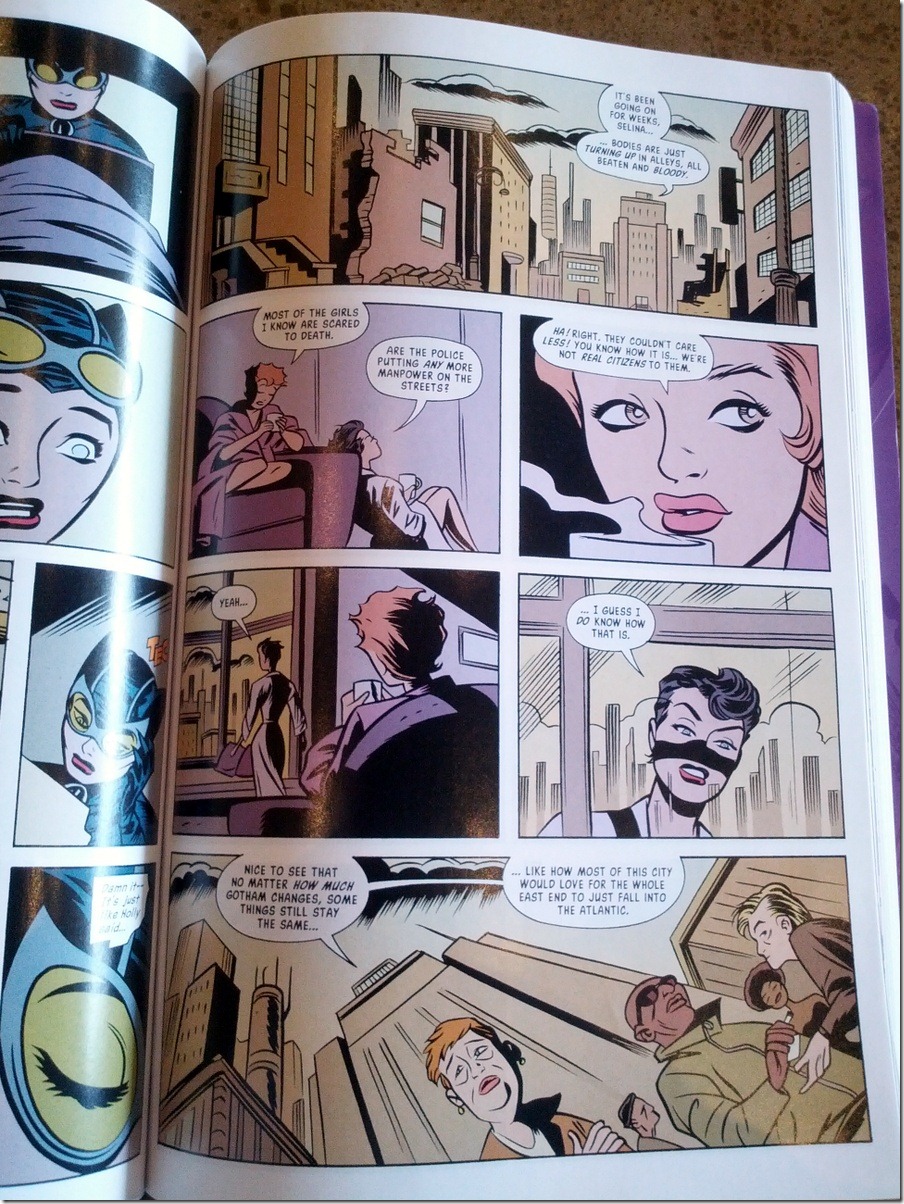

This comic is pretty good. I appreciate the attempts to do some experimenting with the medium. However, I do retain a few qualms. When they did a day in the life story about Selina’s friend, Holly, I was thinking “I hope Brubaker isn’t trying to get us to like her so he can do something horrible to her” and, well, she gets shot at the end of the issue, though it’s not a really serious gun shot wound, more like one of those wounds everyone forgets about once the storyline is over, I’m guessing.

In terms of the experimental tone, however, I’m not sure you can really have your cake and eat it too. If you want to do something experimental involving a day in the life of a character, you probably might want to “experiment” with not going with the obvious dramatic beat of putting the supporting characters in peril? Granted, this is sort of a noir story, and maybe that’s part of the genre, but still…

This can cause the reader to be distracted during your quieter moments, waiting for the shoe to drop. (On the other hand, I can see the counter argument that it’s fine, I guess my main issue is that I saw it coming well in advance…)

Brubaker is also once again hopelessly confused when it comes to superhero morality, having a character lecture Catwoman on needing a motive besides revenge, which she doesn’t disagree with (Err, isn’t that Batman’s motive? I don’t think Brubaker is going for irony.) He does have Catwoman do something more anti-heroish towards the end of the trade, so he may be smartening up.

Still, overall, this is a very fine comic.